“I Believe in Five!”

My strange visit to Wuwu Village⇔

by Michael Krigline, August 2004; www.krigline.com

In the rugged mountains just outside China’s border, the Wuwu tribe live without something that most people believe it’s impossible to live without. The primary peculiarity of this isolated group is that they don’t use the number five. They believe that 2+2=4, but 4+1=6, 3+3=7 and so forth. As a result, if you have six eggs and give three to your in-laws, you have only two to eat (6-3=2). The Wuwu use a complicated system to mark phases of the moon, which allows them to avoid dates with five in them. I’d heard of counting systems that were not based on “ten numbers,” but this was the first time I had seen one.

I considered their “five-less” math system rather odd, but of course it’s perfectly normal to them. They believe that since there is no such thing as five, those who believe in it are the foolish ones. For generations, children have been taught to count using the Wuwu system, and the people manage quite well. I shouldn’t have been surprised, since if everyone believes the same thing (rightly or wrongly), they can get along well and accomplish many things. Relationships with the outside world, however, become troublesome. To avoid these problems, the Wuwu people just choose to remain isolated. Since they live in a remote mountain area it’s easy to stay insulated from others, but the difference between their lives and others nearby is startling.

Think about all the things that only work if you have all ten digits. For example, there are no watches or phones in Wuwu Village, and if there were five-less phones, how could they call people outside their area?

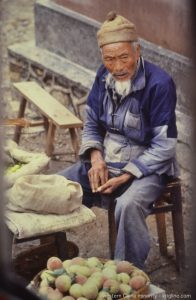

I stayed with a Wuwu man with smiling eyes, a wrinkled brow, and an endearing grin above his long gray beard. The locals called him Loony Shu. As a child, Shu had been sold to a neighboring village as a slave—a common practice at that time. Eventually he earned his freedom and made a small fortune as a businessman (once he learned to use the number five). Upon retirement, Shu felt compassion for the people of his village and dedicated himself to bringing them into what he called “the real world.” He moved back to the village and told fascinating stories about all the things that are possible when you believe in the number five. He claimed that his research showed that the ancient Wuwu people did use the number five, but a powerful tribal leader banned the number long ago and it passed out of use by royal decree.

[See discussion questions 1-3]

Of course, this is how Loony Shu got his nickname. Everyone thinks he’s crazy, since everyone knows there is no such thing as a five. They let him stay because he’s entertaining and because they are pretty sure he really is part of their tribe—he looks like a Wuwu and can still use the language, even after all those years away. But Shu’s stories are so fantastic, and he has all kinds of “things” from the outside that are also too fantastic to comprehend. Children look at the funny images on his clocks and calendars and laugh at the old man. The village elders tried to kick Loony Shu out of town a few times, but he kept coming back. Now they put up with him, so long as he keeps his strange beliefs to himself.

But Shu says it’s too hard to stay quiet. After all, he knows what they are missing. Sometimes when he is out buying vegetables, using the five-less numbering system he learned as a child, he can’t help but break out in a story about the five and how different it could make their lives. He tells them that 2+3 is five not four, and half of seven is not three, it’s 3.5! As tales gush out about phones and other weird stuff, before long he feels a strong grip on his arm. And as they escort him back to his home, he shouts “I believe in five! I believe in five!”

[See discussion questions 4-6]

You can imagine that he doesn’t get many visitors, though last year a small group of curious people started to stop by weekly. Shu answered their questions with patience, introducing them to the 10-digit counting system, and they were beginning to catch on because they were quite bright. But the tribal leaders made the meetings stop. These elders said Shu was allowed to believe what he wanted for himself, but he was not allowed to confuse others. They said the village had a system that worked, and that was good enough. Unfortunately, many of the members of this curious group soon thereafter left the village in their quest for more information (and for modern things like Shu had).

The Wuwu tribe lives in a beautiful place and the people are friendly, but I left Wuwu Village with a sort of sadness. Long ago, someone had convinced them that there was no such thing as a five, and despite the evidence presented by Loony Shu, the people won’t change their counting system. In fact, they are not even allowed to hear the evidence. These people have the right to believe whatever they choose, but I felt sorry for them because I know how much they are missing.

Some of my Chinese friends don’t believe this trip ever took place. They say there is no such place as Wuwu Village. Tell that to the people who live there! They believe they are real, no matter what those outside (who foolishly believe in five) believe about them.

Maybe the take-away from this story applies equally to the existence of the number five, a remote village, God, or anything else. What you believe is not as important as whether or not what you believe is the truth.

Discussion:

- Mr Shu had been a slave, living away from his tribe for part of his life. What affects do you think that slavery had on his life? Explain.

- Throughout history, many leaders have “banned” things. Name some of them, and the result of these bans. Even today, many things are banned in different places. How do we know if such a ban is a good thing or bad thing?

- The article said that “if everyone believes the same thing (rightly or wrongly), they can get along well and accomplish many things.” In history, “everyone” believed that the world was flat, and that slavery was normal. Today, we would judge that “everyone” was wrong; so did those ancient people “get along well and accomplish many things”? Can you think of anything else that “everyone” used to believe, but which today we would judge as being “wrong”?

- Some say that modern “social media” makes it easier than ever to “isolate ourselves” like the Wuwu people do. Do you agree or disagree? What is the danger of isolating oneself from people who are different from us or who believe different things?

- The Wuwu counting system is a central part of their culture’s worldview. Do you think such a worldview could also work in a multicultural, multiethnic city? Why or why not? Most religions are ethnocentric, seemingly designed to help a “closed” group of people stay connected to each other, and separated from others. Are there any religions or belief systems that have adapted well in many different cultures? Explain.

- Why do you think “looney” Shu kept coming back to his village, even though the leaders did not want him there? Can you think of any types of people who are somewhere today where local leaders do not want them? Should they leave or stay? Explain. In your life, what do you “believe” strongly enough that you would keep “going back” in the hope that others would also understand this?

- The tribal leaders stopped curious villagers from going to Shu’s “classes” about the five. What was their reason, according to the article? Do you think these leaders should have done this? Why? What are some things that people in our modern world are told not to study by their leaders?

- What does “brain drain” mean? Why do some of the world’s smartest people leave their home country and settle somewhere else? What could their government do to encourage them to return after gaining a higher education, experience, wealth, etc.?

- Is the author correct in saying that “people have the right to believe whatever they choose”? Explain.

- Do you agree with the statement: “What you believe is not as important as whether or not what you believe is the truth“? What is the danger of believing something that is not true? How do we decide if something is true—or is that even important?

Things on this website ©Michael Krigline unless otherwise noted. For contact info, visit About Us. To make a contribution, see our Website Standards and Use Policy page (under “About Us”).